When community meetings are held to determine priority development projects in villages, in neighborhoods, in schools, in agricultural fields—wherever they may take place—we want to speak the language that is spoken there, spoken every day. The idea of a person or a community of people exploring what they most want in their lives should be as real and as connected to their notion of “self” as possible.

One’s mother language is a language of the heart, and we can express ourselves in that language unlike any other because it is how our deepest contemplation takes place. It is the language of prayer, of mercy and of forgiveness. It is the language of friendship and love. It arises from the concept of the mother, the one who nurtures us as infants, being the one from whom we first hear language and try to articulate what we hear.

Expression in our mother tongue is associated with sustainable development. When we work with community groups through participatory dialogue, we focus on identifying what is most sought and what people want to dedicate themselves to. That kind of introspection should be completely honest, reflecting on our deepest selves in the language in which we are most comfortable. So, language is an essential part of achieving sustainability.

Participatory community planning is a hallmark of civil society organizations dedicated to sustainable development, but it can be challenging when there is the presence of multiple languages of expression. Civil society workers are often in situations where there is no choice but to use their many and varied languages—in Morocco, for example, this will include Arabic as well as Tamazight—to communicate effectively and try to make expression the most personal and closest to what is really felt. This requires movement in and out of languages, creating a climate of multilingualism.

The ideas of multilingualism are actually ancient. In the Hebrew tradition, for example, the highest court had 70 judges to reflect what were considered the world’s 70 root languages. The idea was that if you have each of these essential languages represented, those matters that came before the court would be approached from all different perspectives and points of view in order to come to a more truthful understanding of the subjects being examined.

We should learn as many languages as we can, not just as a skill but as a perception-creating opportunity. Through experiences such as travel, international work, immigration, and personal experience, we develop a multilingual, and thus a pluralistic, perspective. While this contradicts the philosophy that an engaged, connected citizenry benefits from a shared root language, the ability to “code switch” demonstrates a capacity to negotiate the personal as well as the public spheres of higher education, the workplace, commerce, and society. It also allows us to share our cultural and linguistic knowledge with our peers.

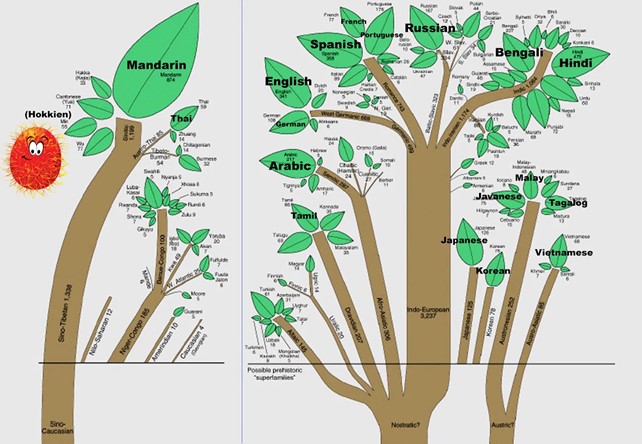

As language is alive and ever-evolving, and as thousands of languages are now endangered, there is also something in the nature of language that must be preserved. We understand that human beings have been on this planet for many tens of thousands of years. Imagine, then, the number of languages that have appeared and disappeared during that time? Today’s languages can be traced to some of them, but some have passed into oblivion. Even the thousands that exist today cannot be compared to the totality of all languages that ever were. Like plant and animal species, biodiversity of languages is becoming rarer and will continue in that trend as speakers of endangered languages pass on or assimilate into larger groups.

We are obliged, then, to make the effort to preserve languages through multilingualism. We need to document and archive them, as through the Endangered Languages Project, but we also must learn and utilize them in real situations through practice and experience. While there is a value to studying in a classroom, most of us learn best by immersing ourselves in the acquisition of new languages. People learn best how to nurture trees or how to deliver legal aid as clinicians and community servants in real situations, and we know that we integrate those skills and abilities and perceptions and absorb them better by actually applying them in the everyday world.

Heartfelt language expression allows for adapted and tailored design of initiatives to meet our human needs, creating the basis for their sustainability. Multilingualism gives us the range of views we need for more complete understanding, followed by decisions that are considerate of the range of factors that are behind (and surround) our lives’ conditions. Diving as well as we can into our home languages and those spoken around us preserves them on earth and avails us of the richness of symbols and knowledge that they carry.

Dr. Yossef Ben-Meir is President of the High Atlas Foundation in Morocco. Professor Ellen Hernandez teaches in English at Camden County College in the United States.