In observance of International Migrants Day, it is important to acknowledge the need for accessible legal aid for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers and the role of local youth in creating a welcoming environment. As migrants leave their home countries, sometimes without warning or preparation, many are unaware of their rights in host countries. Student-led legal clinics provide these vital services while engaging students and other community members and creating a basis for intercultural understanding and support.

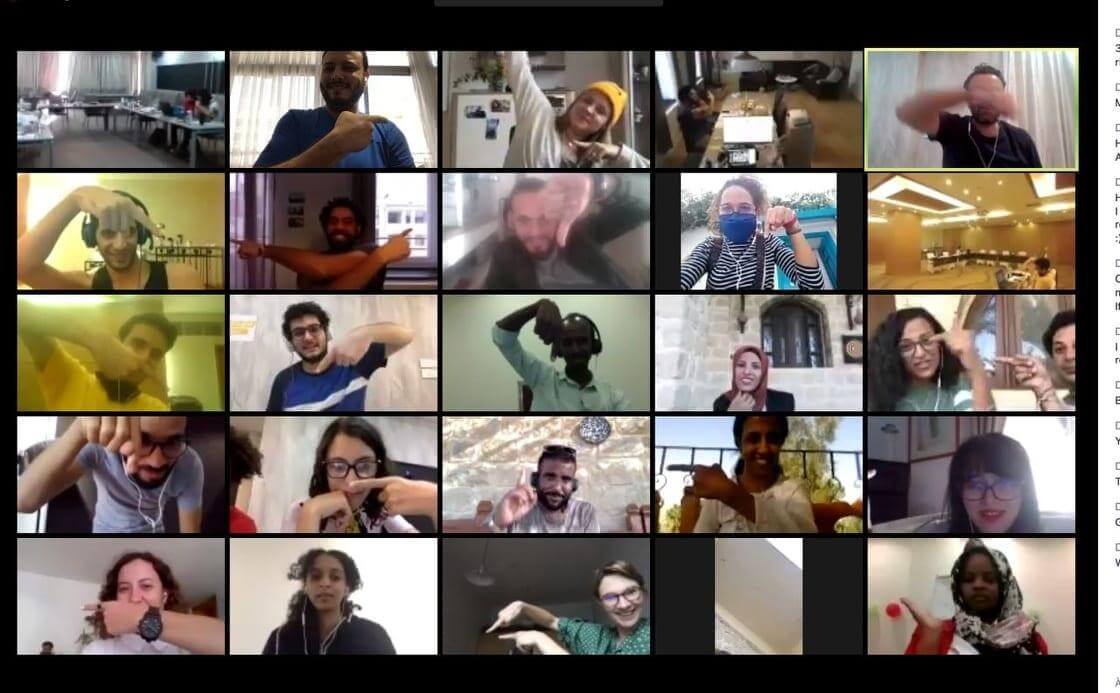

In late November, in partnership with the High Atlas Foundation, the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the student-run Clinique Juridique de la Faculté de Droit at the Faculty of Juridical, Economic, and Social Sciences at University Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah in Fes, Morocco, held a series of training courses for student clinicians on issues related to migration. Students engaged with experts on topics such as the current legislation on asylum in Morocco and international frameworks, including the 1951 Refugee Convention, and the work of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

In tandem with their university curriculum, these sessions give students practical information for use in their work as practitioners of pro bono legal aid for people in vulnerable situations in the Fes-Meknes region. Alongside service-delivery and advocacy activities conducted within the framework of the legal clinic, these organizations are creating an Integration Hub, which will offer capacity building for migrants within the region to encourage integration and coexistence.

Shifting Migration Routes

Traditionally, Morocco is an emigration country, yet it is becoming a destination for many sub-Saharan migrants travelling north to escape conflict and poverty. Moroccan youth facing poor economic prospects at home emigrate to Europe, and many find work as agricultural laborers in Spain. However, irregular migration into Europe has become riskier as closures and increased policing along the Spanish-Moroccan border have forced migrants to turn to smuggling and sea routes.

As conflicts erupt along traditional migration pathways, migrants are seeking out new, alternate routes. Before its civil war began in 2014, Libya was a destination point for many sub-Saharan migrants in search of labor or a way to cross over to Italy by sea. Yet as conflicts make travel more dangerous, routes have shifted west, favoring Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. As a result, Morocco has seen a surge in the numbers of migrants seeking asylum and better employment opportunities.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), 100,000 migrants and refugees live in Morocco, while other estimates suggest the number of undocumented migrants in the country may be in the hundreds of thousands.

Moroccan Migrant Legislation

In response to the large number of undocumented immigrants living in Moroccan cities like Rabat and Casablanca, the Moroccan government conducted two regularization processes for asylum seekers in 2014 and 2016, giving residence permits to over 50,000 refugees and asylum seekers.

Morocco has signed several international conventions focused on refugees and asylum seekers, beginning with the Refugee Convention in 1951 and its Protocol in 1967. The National Strategy on Immigration and Asylum (NSIA), adopted in 2014, allows Morocco to receive and house refugees recognized by the UNHCR. The majority of the 6,656 refugees residing in Morocco are Syrians (about 55%) who are protected from refoulement and expulsion.

Yet despite national and international legislation, the Moroccan government has yet to officially adopt a framework for a national asylum system. While agreements with the UNHCR facilitate entry and protect refugees who have been granted refugee status, those wishing to seek asylum at land and sea borders or in airports are not able to do so without protected status from the UNHCR. Without protected status, those already in the country are at risk of detention, deportation, and labor exploitation.

Reasons for Migration

Facing poor economic conditions at home, migrants from countries suffering from economic downturns or sporadic outbreaks of conflict and instability are seeking employment abroad.

Employment has become more difficult for migrants in Morocco, often who settle in urban areas, which have a higher rate of joblessness (over 16%) than rural areas. By November, the youth unemployment rate reached 12.7%, the highest it has been in nearly two decades. Nearly 1.5 million Moroccans are currently unemployed, many of whom are in the informal sector, where most migrants work.

After COVID-19 restrictions relaxed in early autumn, more than 2,500 sub-Saharan migrants were deported from Algeria and Morocco in response to an increase in pressure from the European Union to reduce irregular migration.

The Mediterranean region has seen an overall increase in the number of migrants risking dangerous routes to access Spain and Italy and gain entrance into the EU. According to the IOM’s Missing Migrants project, there have been 946 mortalities among migrants recorded in the Mediterranean this year, and another 142 between the Moroccan coast and the Canary Islands where rough waters can easily overturn makeshift vessels.

Reducing Irregular Migration

Keeping migrants from risking these dangerous routes and seeking out smugglers will require safe, legal migration pathways, and socioeconomic aid for migrants in transition countries to help them build a base and establish life there.

Development programs and community-based services such as legal aid must also address the possibility of gaps between migration policies. Human rights organizations in Morocco suggest that those who have been given status in previous regularization campaigns may not have maintained that status. National resettlement frameworks need to be recognized at the individual and community level, with proper structures to prevent refoulement and provide aid for migrants denied refugee status by the UNHCR. Access to justice is a human right and democratic necessity, but it cannot be carried out without being put into practice.

The legal clinic in Fes addresses three main components tied to UN principles of human rights and development: it offers legal aid to migrants seeking asylum and reliable information about their status and options, family mediation with a focus on women’s rights under Moroccan Family Code, and it provides young law students practical experience, which is necessary for young professionals facing a job market with a high youth unemployment rate.

The provision of legal aid embodies democratic elements, fundamental freedoms, and human rights. Marou Amadou, the Minister of Justice for the Republic of Niger, said, “People’s aspirations for democracy and development require a ‘true’ rule of law, which is impossible if justice is not accessible to all.”

The legal aid clinic continues to work toward reducing migration-related human rights issues, upholding women’s rights, reducing youth unemployment, and encouraging and facilitating integration of migrants into Moroccan society.

Jacqueline Skalski-Fouts is an undergraduate student at the University of Virginia.