On Saturday, June 19, 2021, Americans officially recognized “Juneteenth” as a national holiday. Most Americans understand the holiday to be a celebration of the end of slavery brought about by the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment. However, the day is actually a recognition of when a remote enclave of enslaved people were informed of the end of slavery more than two years after its declaration and several months before the last states ratified the amendment. The difference between what many consider the holiday to celebrate and what it truly celebrates might seem negligible to some, yet it is certainly a very important distinction, recognizing both a literal and a symbolic moment for people who had been so long denied the right to physical freedom and human dignity as well as the right to education and literacy.

While the Emancipation Proclamation officially outlawing slavery was issued in September 1862, and became effective four months later, it was not until June 19, 1865—two months after the surrender of Confederate forces and the formal end of the U.S. Civil War—that enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, first heard that order of emancipation read aloud by the Union military and became aware that they were free. The following year, freed people in Galveston began what became known as “Jubilee Day,” and observation of the event and its symbolism has grown gradually over the 155 years since then, becoming an officially-recognized federal holiday signed into law in 2021 by President Biden.

This holiday brings to mind the ways in which we experience individual freedom. The people of Galveston in 1865 were unaware of the declaration, unaware of the law, unaware of their status. This was not solely because they were in a remote area some distance from the seat of government but also because they lacked the literacy that would have enabled them to read the posted notices. Without information, knowledge, and learning, how is one to know one’s rights and, with those rights, envision a future for oneself?

In Morocco, there is a vital code that governs family law but that is not known to all of the people it protects—particularly women—depending on whether they live in rural areas and are literate. The Moudawana (Ar. Mudawwanat al-aHwaal al-shakhSiyyah) is the Personal Status Code that encompasses issues of marriage, divorce, inheritance, self-guardianship, and child custody, among others. While first established in 1958 following the nation’s independence from France, the 2004 reform (also enshrined in the 2011 constitutional revision) addresses women’s rights and gender equality in ways that the original did not. Hence it appeased to some extent those feminist and human rights activist groups calling for more widespread attention to socioeconomic inequality and violence against women, groups such as l’Union de l’Action Féminine (UAF or Women’s Action Union).

Life and opportunity are quite different between urban and rural areas of Morocco. Some studies estimate that only about 16 percent of rural women are aware of their rights stipulated in the most recent amendments to the family code whereas 95 percent of urban women know about the code. In fact, five times as many rural women have never heard of it at all. For such women, this lack of awareness is due in a large part to an incomplete formal education since only about one-third of girls continue their schooling beyond primary level and about 60 percent of rural women are not literate. There is a direct correlation between level of education and awareness of rights with 100 percent of those with a secondary education knowing at least something about the Moudawana. Rural women are also less likely to be engaged in local governance or civil society than their urban counterparts and less likely to hold positions in the labor force or have financial independence, all factors that would increase the likelihood of awareness.

How does level of awareness impact Moroccan women? To begin, a girl who does not know that the legal age for marriage was raised from 15 to 18 and that she cannot be compelled by her father into a marriage or that she is legally entitled to schooling might believe she has no say over her own future. Likewise, a woman who does not know that she has a right to her financial assets or a right to enter into a business contract without her husband’s permission might not pursue her dream of financial contribution to her family’s income or financial independence for herself and her children. Furthermore, a woman who is unaware of her rights to a divorce or to child custody might remain in a dissatisfying marriage or, worse, continue to be physically or psychologically abused fearing the loss of her children or believing she has no options or protections.

There continue to be barriers to implementation of the laws in rural areas, as one might imagine. These include inadequate training about the reforms for judges in provincial government, paving the way for individual decisions that revert to older customs, and also the presence of a stronger sense of traditionalism. In rural areas, the more immediate everyday needs take precedence, and concepts of legal equality hold a lower priority than food, clean water, adequate housing, and sanitation. The lack of access to education due to distance or finances and its attendant illiteracy coupled with the home languages of the largely Amazigh population in the rural areas concentrated in the Rif and Atlas Mountains additionally prohibit awareness of laws written in formal Arabic.

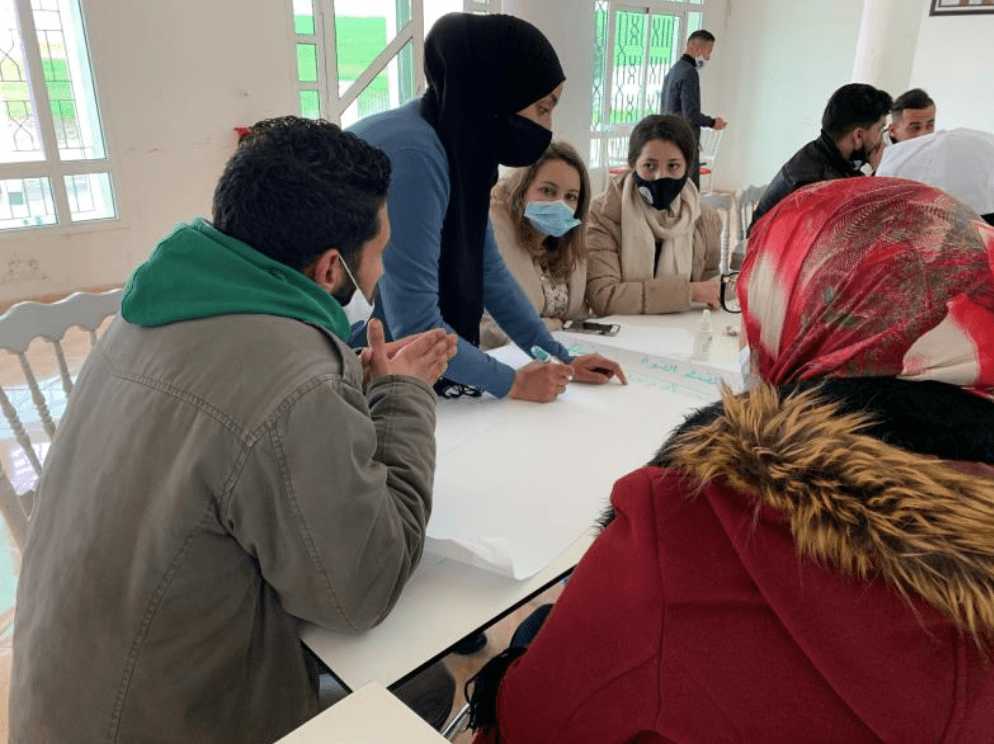

Current efforts to address the lack of awareness are occurring through “Imagine” women’s self-discovery and empowerment workshops led by the High Atlas Foundation, including through its implementation of a Legal Aid clinic in partnership with the Faculty of Social, Juridical, and Economic Legal Studies at University Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah (FSJES-USMBA). The High Atlas Foundation is a Moroccan association and a U.S. 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded in 2000 by former Peace Corps Volunteers committed to furthering sustainable development. HAF supports Moroccan communities in implementing human development initiatives by promoting organic agriculture, women’s empowerment, youth development, education, and health. The Legal Aid Clinic (CFJD)—funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI)—actively engages students in experiential and service learning for the benefit of marginalized communities in the Fes-Meknes region. Recently, for example, one such workshop was held in Sefrou; these four-day workshops include Moudawana rights-based education in the curriculum. Vulnerable populations such as women and migrants provided with legal assistance and information are more supported in knowing and exercising their rights.

To achieve greater gender parity and protection for women, they must first be informed of their rights under the Moudawana. Steady but slow increases in access to formal education must be supported and enhanced to bring the literacy levels of rural women into alignment with their more educated urban peers. Participatory community development that includes women’s empowerment and rights-based education must continue to spread across the nation to give women a voice and a vision and a say over the course of their lives. Training and recruitment and capacity-building must be a priority to increase women’s employment opportunities, and even more importantly for the good of Morocco, presence in economic and political leadership roles. As former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet once remarked, “When one woman is a leader, it changes her. When more women are leaders, it changes politics and policies.” An empowered woman is imbued with self-confidence that benefits her family, her village, and her society. It begins with the knowledge that allows her to imagine her future.

Ellen Hernandez is a U.S. college English professor and a freelance writer.